Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe Now There’s more than one way to become a judge in Indiana.

There’s more than one way to become a judge in Indiana.

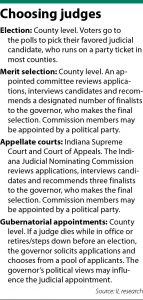

If you want to be an appellate judge, you’ll go through the merit-selection process. If you want to be a trial judge, the voters will elect you, unless your county uses merit selection. There’s also the possibility that you could go through a traditional application process if an unexpected trial court vacancy occurs outside of an election cycle.

Opinions abound as to the merits of the different methods of judicial selection. Some say traditional elections preserve the people’s voice, others say merit selection keeps the judiciary impartial and still others think a hybrid of the two might be best. But for judges who have been through these processes, the end result is what counts most: a judiciary that Hoosiers have confidence in.

With Election Day less than a week away, here is a look at the various judicial selection methods in Indiana and how judges and lawyers view them:

Appellate courts: Merit selection

Jurists on both the Indiana Court of Appeals and Indiana Supreme Court are appointed through a merit-selection process. The Judicial Nominating Commission, led by the Indiana chief justice, reviews applications and interviews candidates, then sends three finalists to the governor, who makes the final choice.

Candidates provide detailed applications to the JNC detailing their personal and professional histories, significant cases and writing samples, among other information. They’re then interviewed at least once and sometimes twice by the commission before sitting through interviews with the governor’s staff.

Judge Edward Najam went through the merit-selection process in 1992, ultimately getting appointed by Gov. Evan Bayh. The Court of Appeals judge says the process is “not for the faint-hearted,” though he thinks most candidates enjoy its rigors.

Najam is a proponent of appellate merit selection, penning an article for the Indiana Law Review in favor of the process. Speaking with Indiana Lawyer, the judge noted that in neighboring Illinois and Kentucky, appellate judges run in partisan elections, resulting in millions being spent on advertising.

“That’s a real distraction,” Najam said, adding that judicial records can be misconstrued through the partisan election process.

Though governors will often select jurists known to be affiliated with the governor’s political party, Najam has not seen politics bear fruit on the COA. In fact, in his 28 years on the bench, he said he’s never seen a case where politics factored into a decision.

Voters have some say in Indiana’s appellate judiciary, though. Appellate judges face retention votes in the first general election after their appointment, then every 10 years after.

Trial courts: Elections

Trial courts: Elections

For most Hoosiers, trial court judges are elected, though even judicial elections vary. Judges in Vanderburgh County, for example, run in nonpartisan elections, while Marion Superior courts previously used the now-defunct “slating” system where candidates required the support of their political parties.

Retired Judge Daniel Pfleging of Hamilton County has been through multiple judicial selection processes, including elections. He also interviewed to become a trial court magistrate and was a finalist to succeed a retiring judge.

Ultimately, Pfleging was successful in his 2005 election bid for Hamilton Superior Court 2, where he served for 10 years until 2016. He faced three primary challengers before facing the Democratic incumbent, including one commissioner and two prosecutors.

Hamilton County is traditionally known to be conservative, but Pfleging says it was his experience, not his politics, that led to his success. In the primary, for example, he focused on his experience working with multiple courts in multiple practice areas as a magistrate judge, as opposed to the commissioner who worked with only one court and the prosecutor who had never tried a divorce case.

Pfleging was unopposed after his first term, then decided not to seek a third. He sees value in the election process because it allows the public to have a voice.

Marion Superior Judge David Dreyer has run for office four times, though his campaigns were not traditional. Rather, because of Marion County’s former slating system, his focus was not on winning the most votes but instead on not getting the least votes.

Under the slating system, both parties would put forward candidates for the primary, and an equal number of candidates from both parties advanced to the general election. There, voters would be asked to vote for both Republicans and Democrats, but there would be more candidates than open seats available. Thus, the lowest vote-getter would not take the bench.

Though slating was ultimately deemed unconstitutional, Dreyer said the process worked for him. Rather than having to focus on an opponent, he could focus on meeting voters and answering their questions.

Marion County has since moved to merit selection modeled after what’s done on the appellate courts, a move Dreyer described as disappointing. While he thinks merit selection works for the appellate judiciary, he worries that the process at the trial court level does not provide enough transparency given the close relationship between judges and their communities.

Marion County has since moved to merit selection modeled after what’s done on the appellate courts, a move Dreyer described as disappointing. While he thinks merit selection works for the appellate judiciary, he worries that the process at the trial court level does not provide enough transparency given the close relationship between judges and their communities.

Merit selection in Marion County also includes merit-based retention recommendations from the local commission. To Pfleging, the best system is probably a hybrid between an initial election to the bench followed by subsequent retention votes.

Trial courts: Merit selection

In addition to the Indianapolis courts, judges in Allen, Lake and St. Joseph counties are appointed through merit selection processes. Local commissions are comprised of lawyers and community members representing both political parties, and the county processes are very similar to appellate selection.

At first, Chief Judge Elizabeth Hurley of the St. Joseph Superior Court thought her appointment was the exception to the rule — that is, she didn’t believe politics played a role in the decision to put her on the bench. But as she’s talked to others involved in the selection process, she’s come to believe the rule — that politics play a role — is actually the exception.

That’s because Hurley was then-Gov. Mike Pence’s first judicial appointment as Indiana’s Republican governor. Both her career and her family, however, have ties to local Democratic administrations.

“I have always thought that both Republicans and Democrats who assumed that the process was highly political must have been very surprised by my appointment,” she wrote in an email to Indiana Lawyer.

South Bend lawyer Doug Sakaguchi serves on the St. Joseph County Judicial Nominating Commission, though he wasn’t on the commission when Hurley was appointed. There are statutory factors that commissioners must consider when making recommendations to the governor, Sakaguchi said, the most important of which, in his opinion, are intelligence, experience and temperament.

Like Najam, Sakaguchi appreciates the merit selection process for its lack of political campaigning. There may be no such thing as a perfectly objective judge, he said, but even the best jurists don’t need to deal with real or perceived influence from campaign donors.

To Sakaguchi, merit selection strikes a balance — the most qualified candidate is selected, then is held accountable through retention and surveys of judicial performance among the local bar.

Gary lawyer Shelice Tolbert is a brand new member of the Lake County Judicial Nominating Commission, but she’s seen evidence of the commission’s previous work in the judges she practices before. She likes merit selection because it allows practitioners who are likely familiar with candidates’ professional experience to assess that experience.

“That’s not saying that elections don’t bring about people who can learn from these positions,” she said. “… But popular votes don’t always tell the true tale.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.