Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowA study by the Indiana Public Defender Commission is highlighting what officials say is a flawed system that encourages contract public defenders to increase their private caseload to cover their overhead costs, which eat the bulk of the compensation they receive for representing indigent defendants.

The report, “Indiana Public Defense Overhead Costs,” focused on attorneys across the state who do public defense work in commission counties. These counties comply with commission standards and, in return, receive a partial reimbursement from the commission to pay public defenders.

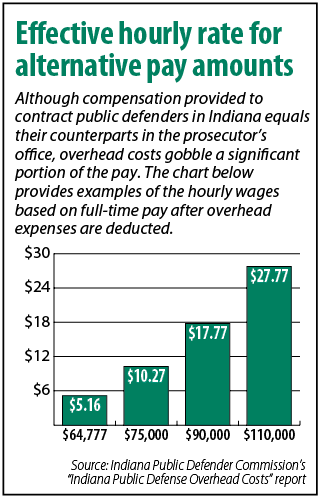

Lawyers who signed full-time contracts with the counties to handle public defense cases received a median yearly salary of $64,777, according to the report. Of that compensation, a median $54,455 went toward the expenses of running their own office. This left take-home pay of just $10,322, which calculates to an hourly rate of roughly $5.16 for a 40-hour work week.

Derrick Mason, senior staff attorney at the commission, said the study shows contract public defenders are not adequately compensated. As a result, these attorneys are having to take more private cases to, in effect, subsidize the work of representing criminal defendants.

“They’re doing public defense work out of the goodness of their heart,” Mason said.

The commission is now turning its focus to finding a remedy. Although Mason said the report makes clear something needs to happen to correct the pay disparity, he conceded that now may not be the best time to broach the topic. The COVID-19 pandemic has crippled the state’s tax revenue, so requests for adjusting the caseload levels or raising compensation will likely not get much traction.

Still, multiple options are available to address the issue, he said. The commission will spend the next year evaluating potential actions.

“We’ll consider input from a variety of sources, but one thing is clear: It is the responsibility of the state of Indiana to provide effective representation to those who cannot afford it,” Mason said. “Indiana’s county-based system needs more resources from the state.”

Jason Pattison, who is a member of the Jefferson County Public Defender Board and handles conflict as well as overload public defense cases in Jefferson, Switzerland and Scott counties, said the whole dialogue about public defenders needs to change.

Pattison sees county officials as reluctant to raise the pay since they think the money would go toward helping criminals. The conversation needs to be shifted to the core service that public defenders are providing, which, he said, is preserving freedoms against threats from the government.

Pattison wants the conversation to become broader. Defending people accused of crimes helps protect the constitutional rights of all members of the public.

Pattison wants the conversation to become broader. Defending people accused of crimes helps protect the constitutional rights of all members of the public.

“We defense lawyers, public defenders and private attorneys are the only people protecting the ‘freedom’ we all think we enjoy,” Pattison said.

More than money

Under commission standards, the public defender’s compensation has to be equal to what the opposing attorney who holds a similar position in the county prosecutor’s office is paid. However, while the pay may be comparable, the prosecuting attorneys are not having to pay overhead costs such as rent, utilities, health insurance and computers.

Pattison is part of law office of Jenner & Pattison but covers all his own expenses. He views public defender work as providing regular payments to cover the bills but, he said, it has never been a way to make a reasonable living by itself.

Describing himself as a poor boy who knows how to be frugal, Pattison said his overhead, excluding his salary, is about $70,000 per year. This includes the pay for a part-time administrative assistant.

A full-time public defender working on under contract in Jefferson County is paid $73,571.40, according to Pattison. The comparable deputy prosecutors make between $70,702 and $81,863, but echoing the commission’s report, he pointed out the prosecuting attorneys get health insurance, retirement, vacation and an office with all the supplies and equipment provided.

Still, Pattison said achieving parity is about more than money. Prosecutors have access to records online that public defenders do not, and they can call upon their investigators while public defenders must hire their own and can only get the complete record by going to the courthouse and paying for copies. Equality, he said, means having access to the same resources and information as well as getting the same level of compensation.

Mason noted Indiana has dedicated and skilled public defenders, but the burden of covering overhead and the need to have an active private practice to make a living can be unintended consequences.

“… No lawyer that lacks the time or resources necessary can provide each client the justice they deserve and the constitutional protections they are guaranteed,” he wrote in an email to IL. “Insufficient compensation, which encourages taking ever-increasing public and private caseloads, undermines Indiana’s entire criminal justice system.”

Survey insights

The burden of overhead was brought to the commission’s attention by attorneys doing public defender work, according to Torrin Liddell, commission research and statistics analyst. Other states have noted a similar problem and, following the lead of North Carolina and Michigan, the commission did its own survey to determine what was happening in Indiana.

Survey forms were sent in May, June and July 2019, with the goal of reaching the lawyers who take public defense cases such as adult criminal, juvenile delinquency, children-in-need-of services, termination of parental rights and appeals. The resulting report was based on a sample of about 204 attorneys from 50 Indiana counties.

Typically, counties that do not have an established public defender office will contract with local private attorneys to represent people accused of crimes in the jurisdiction. The commission limits the caseload these public defenders can handle as allowing no more than 400 misdemeanors each year and 120 major felonies if the attorney has adequate staff to help.

Data shows that public defenders in commission counties are at 90% or higher of the maximum case load, Liddell said. And, noting the shortfall created by the overhead costs, he reiterated Mason’s main takeaway from the survey.

“The concern is that we’re forcing contract attorney to take a lot of private work in order to just survive,” Liddell said.

Along with the current examination of overhead costs, the commission is preparing to unveil a new study of Indiana’s caseload structure. The “comprehensive report,” which was done jointly with the American Bar Association, is scheduled to be released in mid-July.

That will likely spur more conversation and a search for finding what Liddell said is better than the public defender system Indiana now uses. •

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.