Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe Now The fate of the Department of Justice’s recently proposed federal execution protocol is now in the hands of the Washington, D.C., Circuit Court of Appeals, which recently heard arguments on whether the government overstepped when it created a uniform protocol.

The fate of the Department of Justice’s recently proposed federal execution protocol is now in the hands of the Washington, D.C., Circuit Court of Appeals, which recently heard arguments on whether the government overstepped when it created a uniform protocol.

The case, In the Matter of the Federal Bureau of Prisons’ Execution Protocol cases, 19-5322, was heard by judges Gregory Katsas, Neomi Rao and David Tatel on Jan. 15, with arguments lasting roughly two hours. Melissa Patterson, an attorney for the Department of Justice, urged the appellate court to overturn an injunction prohibiting the government from executing five prisoners, while Catherine Stetson, representing the death row inmates, argued the government’s execution plan was unlawful.

The litigation challenging the planned executions of five inmates on death row at the federal prison in Terre Haute — Alfred Bourgeois, Dustin Lee Honken, Daniel Lewis Lee, Lezmond Mitchell and Wesley Ira Purkey — has been ongoing since late last year after the DOJ’s July 2019 announcement that it would resume federal executions using a single-drug protocol. Judge Tanya S. Chutkan of the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia granted an injunction staying the executions, all planned for December 2019 and January 2020, and the United States Supreme Court declined to overturn the injunction in time for the executions to start.

Mitchell is not party to the lawsuit, but his execution was stayed in a separate matter.

As the D.C. appeals court grapples with questions of statutory interpretation, death penalty experts say they expect the case to return to the justices, who will have to grapple not only with questions about the death penalty, but also with questions about federalism.

Manner vs. method

The crux of the Jan. 15 arguments was the provision of the Federal Death Penalty Act holding that federal death sentences “shall [be] … implement[ed] … in the manner prescribed by the law of the State in which the sentence is imposed.” The key word is “manner,” with the government and the inmates positing different interpretations of how broadly that word should be read.

According to Patterson, the DOJ attorney, “manner” means “method,” such as lethal injection, electric chair or hanging. But Stetson urges a broader reading, saying “manner” also includes details about how the execution should be carried out.

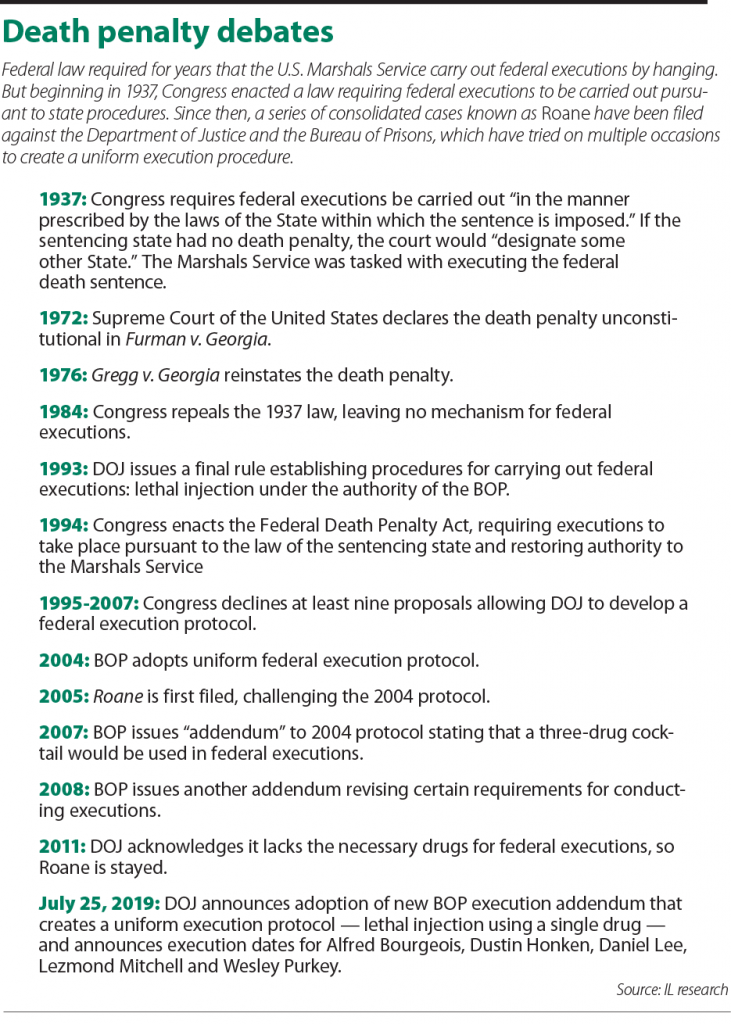

The inmates, in both their briefs and their oral arguments, pointed to the history of death penalty legislation to support their position. As far back as 1937, they said, federal law required executions to be carried out in the “manner prescribed by the laws of the State within which the sentence is imposed” based on the belief that, at least in 1937, state execution procedures were more humane than the federal hanging protocol. The inmates note that the government has asked Congress at least nine times to allow for the creation of a uniform execution protocol, but Congress has never agreed.

The government, however, said historical readings of past death penalty laws have always construed “manner” to mean “method.” The DOJ’s proposed protocol calls for execution by lethal injection, which is the same as all state “methods.”

Further, Patterson said, if state law could control federal executions, then states without the death penalty could stand in the government’s way. The FDPA provides for that scenario by allowing the sentencing court to designate another state that does provide for the death penalty, but Patterson raised the prospect of “recalcitrant states” refusing to cooperate with a federal execution.

“… (P)laintiffs effectively ask this Court to ignore their interpretation’s troubling consequences: that states could be empowered to make it impossible to implement some federal death sentences and that the federal government could not choose execution protocols long urged as more humane than those used by some states,” the DOJ wrote in its reply brief.

But in imposing the injunction, the district judge agreed with the plaintiff.

“‘Manner’ means ‘a mode of procedure or way of acting,’” Chutkan wrote. “The statute’s use of the word ‘manner’ thus includes not just execution method but also execution procedure. To adopt Defendants’ interpretation of ‘manner’ would ignore its plain meaning.”

Federalism questions

During the Jan. 15 arguments, Judge Neomi Rao posed a question that death penalty litigators are also considering: Isn’t the FDPA’s state-law requirement a natural consequence of federalism?

Andrea Lyon, a renowned death penalty defender and former dean of Valparaiso Law School, raised a similar notion. If Congress chose to give states authority over execution procedures, Lyon said, the issue then becomes determining how closely the government must follow those state procedures.

“That is really where the battle line is being drawn,” Lyon said. “How literal must we interpret the statute as written?”

Robert Dunham, executive director of the Death Penalty Information Center, said there is an argument to be made in favor of creating a uniform execution protocol. A uniform protocol might be less confusing, he said, especially considering that not all states allow the death penalty, and many states keep their procedures secret.

But, Dunham added, “that’s a judgment for Congress to make, not something that the DOJ can unilaterally impose.”

“That’s the difference between a republican system of government — that in which power is subject to checks and balances — and a dictatorial government,” he said.

Other arguments

Though the courts up to this point have largely focused on the meaning of the word “manner,” the plaintiffs have raised several other arguments throughout the litigation. One is the role of the U.S. Marshals versus the Bureau of Prisons in federal executions, an issue that also received attention in appellate briefing and arguments.

The FDPA calls on the Marshals Service to “supervise implementation” of federal executions, while the DOJ’s proposed protocol was issued by the BOP and assigns authority over executions to the bureau.

The inmates argue the government’s protocol “disregards Congress’ choice” to give authority to the Marshals by “granting primary authority to a less politically accountable agency in derogation of the statute’s plain text.” The DOJ, however, noted that both the Marshals and the BOP are under the authority of the attorney general, who has the power to delegate authority.

Public interests are at stake in the litigation, as well. Dunham pointed to the question of whether the government’s protocol should have been subject to notice-and-comment rules, rather than being released without public comment.

Relatedly, Lyon said the inmates have an Eighth Amendment right against cruel and unusual punishment, so they have the right to know what the protocol is in order to object, if necessary, on Eighth Amendment grounds.

Dunham expects that once the D.C. Circuit Court has issued its ruling, the litigation will go back up to the Supreme Court.

Lyon noted that in initially denying a stay of the injunction, Justice Samuel Alito, joined by justices Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh, wrote separately to say they believed the government would win its case.

“If the courts treat this as a political issue, there is a very real danger that it could erode the fundamental structure of our democracy,” Dunham said. “My hope would be that the courts would take a look at this dispassionately and take into consideration who is authorized to do what under our Constitution.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.