Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowWhen Victor Quintanilla first began studying the experiences of pro se litigants in remote civil court hearings, he said he and other researchers didn’t think the court experience would be comparable for people using their smartphones as opposed to appearing in person for a civil hearing.

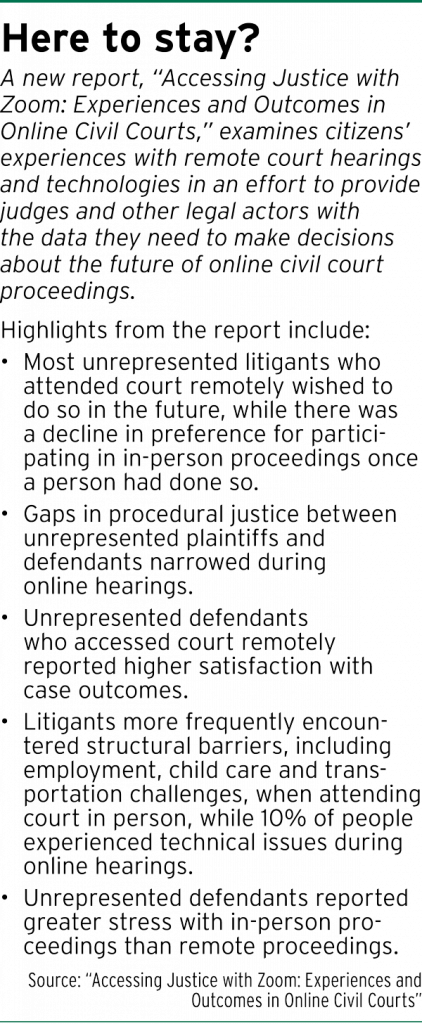

Quintanilla, professor of law and Val Nolan faculty fellow in the Indiana University Maurer School of Law, and his team of researchers produced a new report, “Accessing Justice with Zoom: Experiences and Outcomes in Online Civil Courts,” a comprehensive project involving data from more than 2,000 respondents that found more than 80% of the unrepresented litigant respondents were able to access online civil court proceedings from home or work.

The report, which was spurred by the COVID-19 pandemic and courts’ need to shift to remote platforms like Zoom, also found that pro se defendants in remote hearings reported higher satisfaction with case outcomes than those who attended an in-person hearing.

Also, according to the report, “remote litigants less frequently reported participation barriers than in-person litigants, such as employment, transportation and childcare burdens.”

Also, according to the report, “remote litigants less frequently reported participation barriers than in-person litigants, such as employment, transportation and childcare burdens.”

“I think it revealed the importance of gathering evidence and testing preconceptions,” Quintanilla said.

Quintanilla said he thinks a goal for civil courts should be to have a remote option, as it would offer relief for a lot of Hoosiers called to court.

He also said there are a lot of ongoing discussions in the legal system about, post-pandemic, whether to allow remote options to continue for civil proceedings.

From the report

For the study, Quintanilla and his team recruited 58 Indiana judges across 40 courts and 12 counties, far exceeding the 20 judges initially targeted for the initiative.

One of the things researchers saw in producing the report — which tailored its focus to high-volume civil issues like small claims, evictions, debts and family law — was that there were a lot of unrepresented people coming into civil courts.

Quintanilla said there was an asymmetry between claimants and plaintiffs who were represented by attorneys and defendants who were pro se.

According to the report, in Indiana eviction cases, 70% of landlords who are plaintiffs have representation, while only 1% of tenants who are defendants are represented in court.

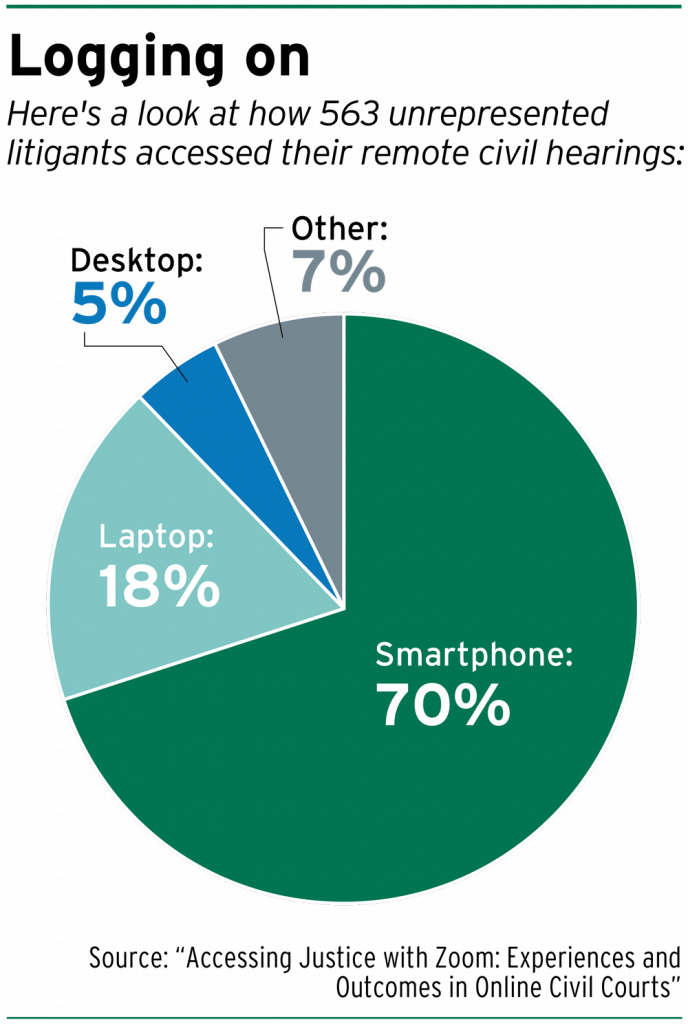

Attorneys appearing remotely were generally doing so by computer, while many unrepresented litigants were using smartphones.

“We were concerned about what the experience would be like, coming on their smartphones,” Quintanilla said.

But researchers found that accessing a hearing by smartphone, in addition to being popular, was not a risk factor.

“I think what our findings underscore for many self-represented, unrepresented litigants the benefits and conveniences of being able to access court remotely are very real,” Quintanilla said.

Other findings note that the stress self-represented litigants experienced while appearing remotely was markedly reduced compared to the stress of navigating and showing up in person. Remote court appearances were also helpful for litigants who couldn’t afford to take time off work for hearings or find child care.

Client benefits

Diane Walker, managing attorney of Pro Bono Indiana’s Bloomington office, said she, like Quintanilla, was surprised by some of the report’s findings.

“It turns out it’s really helpful. People seem to find they get good results,” Walker said of having an option for remote hearings.

Nick Minaudo, a staff attorney for Indiana Legal Services’ Bloomington office, said ILS clients who have used Zoom for initial eviction hearings, on average, prefer remote hearings.

“They very much value the option of a remote hearing,” Minaudo said.

Remote hearings can make some people feel like they can get justice in civil cases without structural barriers, Minaudo said. For example, a lot of people who access the court through remote hearings do so at home or in their cars in the parking lot at work.

Minaudo said a lot of the clients whom Indiana Legal Services assists through its Bloomington office have driving issues and are faced with questions such as whether they should drive to their court hearings on a suspended license.

Minaudo said a lot of the clients whom Indiana Legal Services assists through its Bloomington office have driving issues and are faced with questions such as whether they should drive to their court hearings on a suspended license.

There also occasions when there are technical issues related to remote hearings, Minaudo acknowledged, but he stressed that those kinds of issues are few and far between.

“It seems like overall, litigants are becoming more technologically ready to appear at those hearings,” he said.

Minaudo said he hopes more judges across the state become more open to holding remote hearings for civil cases.

The use of Zoom slows down a normally fast eviction process in court, he said, and help parties come together for agreements that they can both be happy with.

Remote hearings seem to level the playing field and allow litigants to get results they may not have thought were possible, Minaudo added.

Rural impact

Walker noted that most attorneys in Indiana are concentrated in metropolitan areas, with fewer attorneys setting up shop in in rural communities.

Remote hearings, she said, can help organizations like Pro Bono Indiana get more attorneys to handle pro bono cases in those rural areas.

“If you ask someone to do something pro bono and they don’t have to drive three hours roundtrip, they may be more likely to take the case,” Walker said.

Court of Appeals of Indiana Judge Melissa May is part of the state’s Coalition for Court Access rural working group. She said she was also a little surprised initially at some of the report’s findings.

“But after thinking about it, I wasn’t,” May said.

May said there should be more remote civil hearings, noting that a lot of people in rural communities can’t afford to take a whole day off work for an in-person, 20-30 minute court hearing.

But there are also logistics to be worked out.

The use of remote hearings varies county-by-county and often depends on trial judges and their experience levels, as well as the available technology in a given county’s court system.

May said it’s not fair to ask a judge to be a finder of fact and also the manager of Zoom in their court.

“So you have to have staff that are trained on it,” she said.

Courts have the ability to go through the Indiana Supreme Court and ask for grant funding for technology services, May noted. She said the high court has been very helpful to the state’s trial courts with technology funds.

A tool, not a goal

Remote hearings and the use of Zoom are tool for courts to utilize, May said.

But she added, “I think it’s to be used as a tool and not as a goal.”

For example, May said she thinks the use of Zoom and remote hearings would be useful for some civil hearings, but not for civil jury trials. She also said it’s particularly important for criminal defendants to appear in person.

The report’s findings are seen as helping win over some of the people who are skeptical about remote hearings.

May said she thinks the end result of the report will be to help guide trial judges and attorneys in rural counties and show that remote hearings can work.•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.