Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe Now I am often surprised by the frequency with which businesses choose to arbitrate or litigate commercial disputes. Disputes that allege a breach of contract, warranty or the like keep my litigation practice busy, but as a mediator, it seems these types of disputes over the very terms that govern the parties’ business relationship should lend themselves to amicable resolution. Sophisticated parties should be able to privately negotiate and resolve such matters short of litigation or even arbitration.

I am often surprised by the frequency with which businesses choose to arbitrate or litigate commercial disputes. Disputes that allege a breach of contract, warranty or the like keep my litigation practice busy, but as a mediator, it seems these types of disputes over the very terms that govern the parties’ business relationship should lend themselves to amicable resolution. Sophisticated parties should be able to privately negotiate and resolve such matters short of litigation or even arbitration.

It is universal that all business disputes, until resolved, come at a cost to commercial enterprise. No matter how simple or complex a dispute is, while it remains unresolved, it will necessarily deprive all parties of time, money and energy; lower employee morale; negatively impact productivity; and ultimately result in profit losses. Because these types of commercial disputes almost never make good business sense, logic and reason dictate that they should be resolved through negotiation and agreement. Shouldn’t they? The answer is absolutely. It turns out, however, that as with individuals who are in conflict, businesses are not immune from the emotional aspects of human conflict that so often act as an impediment to logical and rational approaches to conflict resolution.

So why, then, is it that commercial parties are so frequently opposed to reasonable, rational and economically favorable resolutions through private decision-making processes? According to British mediator and author David Richbell, “The answer lies not in our lawyers, but in ourselves. For centuries, we have proved ourselves to be a species wholly incompetent at resolving our disputes. In our competitive, combative, and adversarial ways, we strive not only to win, but we go further in wanting utterly to crush and humiliate our opponents: we want to see blood on the walls.” (“How to Master Commercial Mediation: An Essential Three-Part Manual for Business Mediators,” at p. 122.) This is so, according to Richbell, because conflict plays an important and constructive role in all our lives. The cycle of conflict and reconciliation, he says, brings greater mutual understanding, progress and advancement, and results in changes for the better. Id. Conflict also provides a unifying function, promotes bonding and strengthens human associations, leading to greater cohesiveness among diverse groups.

As with other disputes, commercial disputes involve emotional elements because they include allegations of fault. Such accusations usually create hurt feelings. Conversely, when fault is alleged and denied by the opposing party, the denial itself also produces hurt feelings. Allegations and denials take direct aim at one’s self-esteem. “Self-esteem is not confined to individuals … [c]orporate self-esteem, felt through injury to the feelings of executives in relation to their organization can be as powerful … .” Id. at pp. 124-25. Legal advisers unfortunately also are not immune from the emotional response of their clients. “So the first principle with which the psychologically-informed mediator must grapple, is that when parties are in conflict, they do not think or behave rationally but rather are driven by their emotions.” Id. at p. 123.

If we accept that businesses are not immune from the emotional aspects of human conflict, and that the cycle of conflict and reconciliation is necessary to progress and advancement, should not businesses still choose to avoid the costs and risks of formal legal processes as they work through the commercial and emotional aspects of the conflict resolution process? In most instances, the clear answer should be a resounding “yes.”

Mediation arguably is the best method of managing conflict and resolving disputes. Mediation fosters private decision-making in a controlled environment involving an agreed-upon neutral and agreed-upon processes for exchanging information and negotiating a private solution.

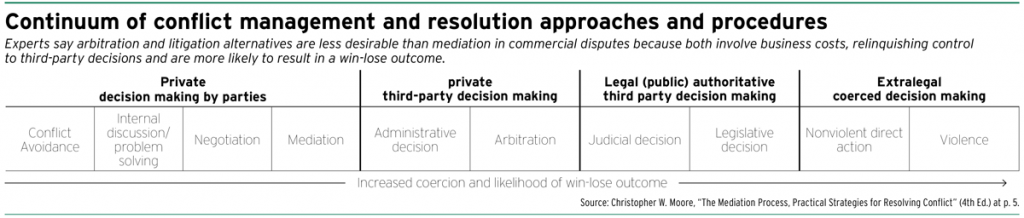

Arbitration and litigation alternatives are less desirable because of the aforementioned business costs, because both alternatives involve relinquishing control into the hands of third-party decision-makers and are more likely to result in a win-lose outcome.

Mediators, moreover, are fully capable of managing both the commercial and emotional elements of the conflict resolution process in a private setting. A mediator who understands the strength of influence that emotions may have on the parties can help them navigate past the irrational behaviors and predicaments that emotional responses cause and improve the chances for a successful resolution. Emotions can trigger common reactions in mediation: storylines of good versus evil; negotiating strategies requiring that the other side make the first move; a refusal to share or exchange critical information; and a need to have the last word. (Richbell, “How to Master Commercial Mediation,” at p. 125.) Effective mediators manage such reactions with active listening techniques. Active listening is designed to satisfy the parties’ respective needs to be heard, understood and accepted. When properly used, active listening fosters a confidence in the parties that the agreement they have reached is a good result. As such, active listening is the key to minimizing emotional impediments to settlement.

Active listening involves: (1) facing the person who is speaking, making eye contact and focusing on the information being delivered; (2) suspending judgments during the information gathering process; and (3) repeating the substance of information delivered both to confirm that it was accurately understood and to build confidence in the parties that what was said was heard.

According to Moore — who was trained by the U.S. Federal Mediation and Conciliation Service and the American Arbitration Association — in his book, “The Mediation Process: Practical Strategies for Resolving Conflict” (4th ed.), “Active listening helps legitimize for a party the existence and expression of emotions. It may also help him or her to feel heard and better understood and gain insight into his or her feelings. In addition, it provides an opportunity to respond to what the listener has heard and restate it back to them, thus clarifying any misunderstandings.” Id. at p. 254. Satisfying the need to be heard, understood and accepted is one of the reasons that the mediation process can and should take considerable time before negotiations even begin. The mediator should be taking active responsibility to understand the content of what each party is saying, as well as the emotions that go hand-in-glove with the content being received. In so doing, the mediator is in a position to use the information shared to move the conversation forward and drive the parties to create their own resolution, which in turn may help them to feel they have overcome any emotional barriers that otherwise would have driven them to want to continue to fight.

As you prepare for your next commercial mediation, consider privately disclosing to your mediator any strong emotional responses your business decision-makers have experienced that may impact negotiations. Doing so may allow your client to feel heard, understood and accepted and eliminate emotional impediments to a well-crafted private settlement.•

__________

Peter French is a partner in Taft’s Litigation group. Reach him at [email protected]. Opinions expressed are those of the author.

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.