Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowSince the spring of 2020, the number of fentanyl overdoses has exploded in Indiana and across the country.

With the highly lethal synthetic substance being trafficked across state and country borders, often laced with other drugs on the black market, law enforcement and public health experts are trying to keep up with its increased use and distribution.

Overdoses rising

According to the Drug Enforcement Administration, fentanyl overdoses are now the No. 1 cause of death for Americans between the ages of 18 and 45.

As part of the recent “One Pill Can Kill” initiative, the DEA and its law enforcement partners seized more than 10.2 million fentanyl pills and approximately 980 pounds of fentanyl powder during the period of May 23 through Sept. 8.

In 2021, a record number of Americans, 107,622, died from a drug poisoning or overdose, with 66% of those deaths attributed to synthetic opioids such as fentanyl.

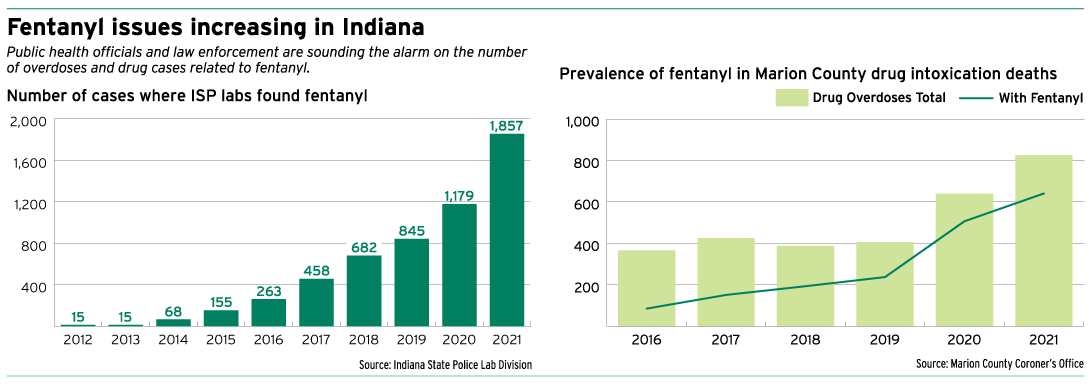

According to the Indiana Department of Health, 2,554 Hoosiers died of drug overdoses in 2021, and more than 70% of those deaths were caused by fentanyl and other synthetic opioids.

The 2021 annual report by the Indiana State Police Laboratory Division revealed the number of fentanyl-related compounds submitted increased from 1,179 cases in 2020 to 1,857 cases during 2021. In 2012, that number was 15.

Douglas Huntsinger, executive director for drug prevention, treatment and enforcement for the state of Indiana, said awareness and access to naloxone are two important factors in the short term to help combat fentanyl overdoses.

“(Fentanyl distributors) are not sophisticated pharmaceutical manufacturers … they are using kitchen-grade blenders to mix fentanyl in with other substances,” Huntsinger said. “You may have one pill that looks like a Percocet that has no fentanyl in it and you may have another pill that resembles a Percocet that is 100% fentanyl. It’s an incredibly dangerous time to be doing drugs.”

U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of Indiana Zachary Myers said a majority of the fentanyl in the state can be traced back to Mexico. Myers said fentanyl compounds are largely being shipped from China to Mexico, where it is then processed in labs before being trafficked into the United States.

From Jan. 1 to Aug. 1, over 2,500 Hoosiers died from drug overdoses, the vast majority from fentanyl and similar drugs, according to Myers.

Buckling down on dealers

Over the last few weeks, Myers’ office has sent out multiple press releases highlighting arrests and convictions involving fentanyl distribution.

Myers told Indiana Lawyer he has directed his office to “prioritize prosecutions involving fentanyl.”

“Because with our limited federal resources, we have to pick and choose, where do we think we can make the biggest impact?” he said. “And I think in the world of drug trafficking, there’s no question that from a public safety standpoint, from the needs of the community, we have to fight the fentanyl crisis.”

One recent case highlighted by Myers’ office was the conviction of California man Felix Beccera-Aguilera, who was arrested in Hancock County by ISP in 2021 and found to have 8.5 kilograms of fentanyl. One kilogram of fentanyl has the potential to kill 500,000 people.

Beccera-Aguilera, who was trafficking the drugs to Philadelphia, was sentenced to nearly four years in federal prison.

Multiple fentanyl distributors from Indiana have also recently been federally indicted, according to Myers’ office, with sentences ranging from 10 to 12 years.

ISP Sgt. Taylor Shafer, who has worked in the Drug Enforcement Section for 10 years and also works with federal law enforcement, helps lead undercover drug busts.

Shafer said he has seen an “explosion” in the number of fentanyl tablets over the last couple of years, and that the lethality of fentanyl — as well as it being synthesized with other drugs — makes it unique.

State court charges

In 2018, the Indiana Legislature passed a law, found at Indiana Code § 35-42-1-1.5, making it a Level 1, Level 2 or Level 3 felony to commit dealing in a controlled substance resulting in death.

According to the Indiana Prosecuting Attorneys Council, from July 1, 2018, to July 25, 2022, there were 100 total dealing in a controlled substance resulting in death charges filed, with 97 of those as Level 1 felonies and the remaining three cases as Level 2 felonies.

Of the 97 Level 1 felony cases, there have been 21 guilty, one not guilty and 63 pending outcomes, IPAC told IL. For the Level 2s, two have been found guilty and one was pending.

IPAC recently held a summit in Indianapolis focusing on those types of cases to allow prosecutors and law enforcement officers from around the state to learn how to build successful cases, an IPAC spokesperson said.

Rick Frank, drug resource prosecutor for IPAC, said in a statement that the dealing-resulting-in-death charges are “difficult cases to put together because there are often very few, if any, witnesses.”

“Law enforcement and prosecutors have to use evidence like cellphones to essentially work backward on a case from when the overdoes occurred to try and figure out where the drugs came from — and from whom,” Frank said. “To build a case establishing proof beyond a reasonable doubt can sometimes be very time-consuming, tedious and difficult. But we think these are very important and worthwhile cases that can bring some kind of justice and closure to the victims’ families.”

The difficulty of securing a guilty verdict in a dealing-resulting-in-death case was recently illustrated in a case that made it to the Court of Appeals of Indiana.

In 2021, Justin Yeary of Noblesville was convicted of Level 1 felony dealing resulting in death after he sold drugs to Tyler Humphrey, which resulted in the 23-year-old man’s death.

Yeary was initially sentenced to 35 years, with 25 years executed in the Indiana Department of Correction, three years served in community corrections and the remaining seven years suspended, with four of those years served on probation.

However, in April, the COA reversed and remanded to the Hamilton Superior Court, finding, “Due to the ambiguity regarding precisely what drugs and in what quantities Tyler took over the time period leading up to his death, the jury’s verdict likely turned on its understanding of the legally required causal connection between the drugs Yeary sold Tyler and Tyler’s death.”

The COA left open the possibility of a retrial due to other significant evidence, however, including evidence of text messages sent and received by Humphrey.

According to court records, the case was reopened July 1. A final pretrial hearing is scheduled for Nov. 10, and the docket shows a jury trial on the calendar for Dec. 5.

Enhanced penalties?

Last month, Sen. Marco Rubio, R-Florida, introduced a bill that would make distributing fentanyl a felony murder. If the bill were to become law, capital punishment would be on the table for those charged with the crime.

Sen. Mike Braun, R-Indiana, is cosponsoring the bill.

“Fentanyl is killing young Hoosiers and cutting a path of destruction through the Midwest,” Braun told IL In a statement. “If you are peddling this poison, you should pay the price.”

A spokesperson for Sen. Todd Young, R-Indiana, said that fentanyl is a “very important issue to” to the senator and pointed to statements he made during a May 11 press conference. The spokesperson said Young has not had a chance to review Rubio’s bill.

Brandon George, director of the Indiana Addiction Issues Coalition, said he does not want to see Indiana creating policy based off individual drugs.

“What I would like to see … is more of a public health response to the fentanyl and overdose crisis than a public safety response,” George said, referencing a new report by the Indiana Behavioral Health Commission. “And we keep leaning, almost like a visceral reaction, to go to public safety versus really treating it like a health care issue.” •

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.