Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowFew things about Indiana’s 2020 mid-summer bar exam were like those that had come before.

The traditional two-day test was reduced to a one-day ordeal. It contained only short-answer and essay questions developed by Indiana bar exam officials and did not include the Multistate Bar Exam, the multiple choice test, or the Multistate Performance Test, the skills test, which are formulated by the National Conference of Bar Examiners and given nationally.

The traditional two-day test was reduced to a one-day ordeal. It contained only short-answer and essay questions developed by Indiana bar exam officials and did not include the Multistate Bar Exam, the multiple choice test, or the Multistate Performance Test, the skills test, which are formulated by the National Conference of Bar Examiners and given nationally.

Applicants did not gather in one central location to take the test in person but took the exam remotely from their homes. Faulty exam software forced Indiana to delay the exam one week to Aug. 4 before tossing the software altogether in favor of just sending the questions and receiving the answers through email. The test was not proctored and applicants were allowed to consult their notes and class materials.

Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, Indiana made dramatic changes to its law licensing test. The goal was to keep the applicants safe and to ensure the newest crop of law school graduates could complete the final requirement of their education and begin practicing as soon as possible.

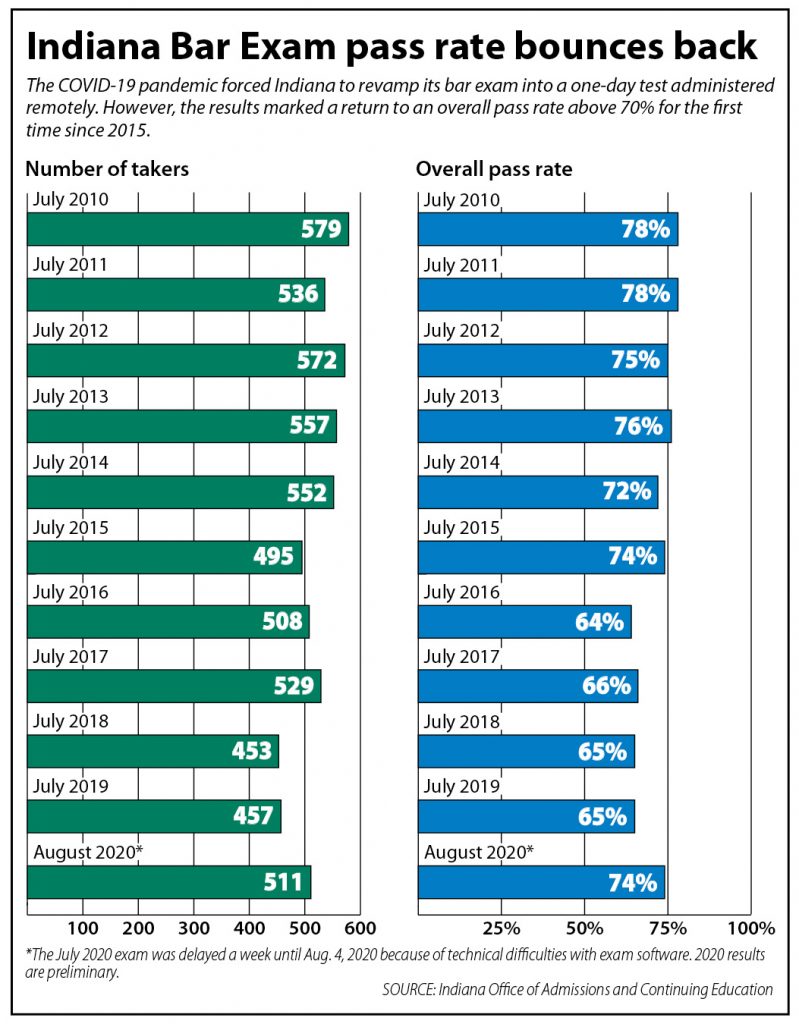

These unprecedented changes resulted in a passage rate not seen in five years.

The overall passage rate for the Indiana August 2020 bar exam reached 74%, about 10 percentage points higher than the overall pass rate for the previous four July bar exams. Likewise, 84% of those taking the test for the first time passed while 53% of the repeat takers were successful, the highest rate for repeaters since 54% passed the February 2015 bar.

Comparatively, the overall pass rate for the bar exams administered in July 2016 through July 2019 hovered around 65%. Roughly 75% of the first-time takers passed during that same period while repeat takers struggled and bottomed out at 23% last year.

“I think the lesson is that innovation should not be scary,” said Nicholas Bauer, a 2020 Indiana University Maurer School of Law graduate. “That the Indiana Supreme Court was willing to be innovative is something I’m really thankful for as a bar candidate.”

The coronavirus outbreak robbed the Class of 2020 of a last semester of law school and graduation ceremonies. Bar applicants also said it raised the stakes of the 2020 bar exam much higher than normal, which only added more angst to the already extremely stressful circumstances.

However, applicants liked being able to take the exam remotely. The ongoing public health emergency confined the 2020 candidates to their homes, but some said even if the virus is contained and in-person testing becomes possible, Indiana should continue using the remote format for the licensing exam.

Nell Collins, a 2020 IU Maurer graduate, is now living in Fort Wayne as she begins a judicial clerkship with the Allen Circuit Court. An in-person bar exam, she said, would have taken her from the comfort of her own environment and placed an additional burden on her of having to travel to the Indianapolis area and to find a place to stay for a few days. Moreover, she was contending with a back injury, so she was able to physically relax and even take part of the exam while lying down.

Bauer also appreciated not having to leave his Bloomington home. He sat in his own chair at his own desk in his own office with the temperature set to his liking. Snacks and water were close at hand, the room was quiet and the risk of exposure to COVID-19 was zero.

“If you don’t live in the city where the test is given, a lot of logistics are involved” to get there and get settled, Bauer said.

Countering skeptics

Applicants point to the improved passage rate as evidence that the changes to the exam, particularly giving it remotely, were beneficial. They know other attorneys may be skeptical of the 2020 candidates’ qualifications because they took the bar at home with open books, but they are confident in their abilities to be good lawyers.

“I will give a hearty laugh and explain why this was so different from other bar exams,” Collins said of how she would respond to anyone who questions her credentials.

Indiana was planning to administer the August 2020 bar exam using the Exam360 software from ILG Technologies, the same computer program the state has been employing since the February 2018 bar. However, the software repeatedly malfunctioned, and when the company was unable to provide a fix, the Indiana Supreme Court decided to send the questions through the more mundane but considerably more reliable technology of email.

The Supreme Court also gave the applicants permission to consult class materials, textbooks and other resources as they answered the questions. As the original July 28 test date approached and the software troubles continued, many applicants sent a letter to the Indiana justices asking for an open book format.

They argued consulting outside resources mirrors the practice of law. Attorneys are not asked multiple choice questions and they are expected to research to make sure they understand the topic before advising their clients. Also, the applicants noted, while they did look up different things during the exam, time was short and they still had to be able to spot the issues, make the analysis and compose answers that were on point.

“If you hadn’t been studying all summer, open book would not have helped,” said Rachel Hogenkamp, a 2020 graduate of Indiana University Robert H. McKinney School of Law. “It made the playing field even for the folks who had to deal with extraordinary circumstances this summer.”

The stress of taking the bar during COVID-19 was increased when the Indiana Board of Law Examiners had to abandon plans to proctor the test-takers using external cameras. With no one watching, applicants feared others would take advantage of the opportunity to cheat.

Collins does not question the integrity of her classmates, but just the thought that some might surreptitiously consult their notes created more psychological agony. The pressure to pass the bar on the first try was higher this year because applicants felt they had to have their law licenses to better weather the pandemic-induced economic upheaval.

Although she would not have been able to live with herself if she had cheated, Collins said open-book alleviated her worries that following the rules might have put her at a disadvantage.

Moving forward

The August 2020 bar exam was starkly different from previous exams, but the applicants’ reaction upon learning they had passed was the same as it has always been.

“We were like a couple of teenage girls screaming,” Hogenkamp said, describing her post-results phone conversation with her best friend and classmate.

Applicants were elated because having passed the bar means they can, at last, begin careers that will enable them to help people. Hogenkamp will be a staff attorney for Indiana Legal Services in Indianapolis and Bauer will join his father, Jawn Bauer, at Bauer and Densford in Bloomington.

As the Class of 2020 moves forward, they highlight different lessons from this year’s exam that they hope will shape the exams that come after.

Hogenkamp pointed to the success of the collaboration between the applicants and the Supreme Court as plans for the August 2020 test were made and remade. The applicants gave their input and explained their needs, which helped the Supreme Court develop and administer an exam that she is confident ensured the test-takers have the competency to practice law.

Collins said the pandemic exposed the flaws in the bar exam. Namely, those who struggle with child care or have health issues are adversely affected because they do not have the time or resources to adequately prepare. People without a support system work as hard, if not harder, she said, but their extra responsibilities put them at a higher risk of not passing.

“The test is leaving people behind who would be good lawyers,” Collins said.•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.